Prince Comes Back To Warner Bros And Shows The Boundaries of DIY

The rallying cry of many musicians today is “Do It Yourself” or DIY, meaning that it’s now possible to do so much of the grunt work necessary to make it without the help of a record label. For instance, you don’t need a label to act as a bank to supply money for recording any more, since most every musician has a studio at home that’s far more powerful than what The Beatles used in their heyday. You don’t need the label to manufacture your product, since it’s now possible to print limited runs of CDs if necessary, and virtual products cost very little to distribute. As far as promotion, social media and YouTube play such a big part in getting the word out, and so much of that can be done directly by the artist.

DIY is indeed a viable option until the point where the artist rises to the level of star, then all DIY bets are off. In order to break on through to the other side of international superstardom, the marketing infrastructure provided by a major record label is almost a necessity. A DIY artist can opt to try to reinvent the wheel, or go to a label with experience and expertise to make things happen on a larger scale.

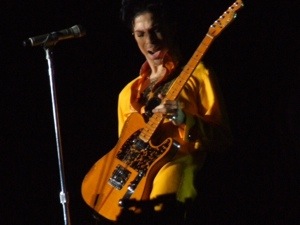

This is exactly where superstar Prince finds himself, as his recently announced new deal once again returns him to the Warner Music fold, a surprising move that many industry observers thought could never happen. Warners was the label that originally launched Prince into stardom, but the falling out between the parties became so vile that Prince labeled himself a “slave,” then changed his name to that unpronounceable insignia as to create a new trademark that would not promote his previous Warner releases.

The problem is that the years hence haven’t been that great to the Artist financially. For a major artist, Prince hasn’t sold all that well since he’s gone out on his own. According to Soundscan numbers posted by Billboard, the artist has sold 18.5 million albums in the United States since 1991, but 14.3 million of those were with Warners. Most of an artist’s income comes from touring and merchandise sales but the fact of the matter is that he hasn’t had a big blockbuster tour in a long time either. There’s nothing like an cash infusion from a deal with a major label, even if it is an old nemesis, which was probably a good enough reason in itself to do the deal.

It’s also been said that in the deal with Warners, Prince will get back ownership of his old Warner Brothers masters, which include some of his most loved albums. The fact of the matter is that he would soon have the ability to get them back under the Copyright Revision Act of 1976, which states that any master recording copyright can be terminated 35 years after it was granted. The law went into effect in 1978, which happens to be the same year that Prince’s first album came out. All of his albums are about to come back to him in the upcoming years anyway, so that means there must be a better reason than that to do the deal.

The fact is that being out on your own can be liberating, but a tough go at the same time. The economies of scale that a label has don’t exist for a DIY artist, even one as big as Prince, and the marketing benefits that today’s social media platforms offer take time and a specialized infrastructure to take advantage of. There’s a lot of additional work required from an artist that goes beyond simple music creation, so much so that the comfort of a major label begins to look pretty good after a while. A great example of this is Nine Inch Nails founder Trent Reznor, who’s as savvy a social media entrepreneur as there is, and who’s now back with in the major label fold with Columbia as well. Ceding control equals more time for the things that artists love the most, which is making music.

With a new album, an upcoming tour, and a 25th anniversary Purple Rain box set ready to drop, there’s a lot on the line for The Artist. Prince, and Warner Music, can make a lot more money working together than they can apart. If that isn’t a good reason to bury the hatchet, nothing is.